Thesis 1: The future of Russian governance is neither necessarily democratic nor strictly non-democratic. This choice is likely too binary for Russia’s extremely complex realities. Instead, a future Russia may well be – and perhaps should be – decidedly hybrid, drawing promiscuously on the best in 21st century structures and practices from around the world.

Russia is a young country – even if most people, including many Russians, forget that this Russia, in its post-Soviet incarnation, is only just completing its third decade. It is therefore naturally still solidifying and indeed inventing, improvising and legitimating its governing institutions, not to mention forming (with inconsistent success) its future political elites. The country’s constitutional youth, coupled with its present unique internal and international pressures, means that Moscow can look non-dogmatically westward and eastward alike (and elsewhere besides) to adopt the best in governing approaches, even as it indigenizes these and ends up with its own idiom – as is, by history and mentality alike, the Russian wont.

Let me propose that there are two dominant governing paradigms in the world today – on the one hand, the democratic tradition or, more tightly, what I would call “argumentative governance”; and on the other hand, “algorithmic governance”. “Argumentative governance” prevails in the presumptive West – the deeply democratic countries of North America, Western Europe and indeed much of the European Union, Australia, New Zealand and perhaps also Israel. “Algorithmic governance” is led almost exclusively by the dyad of modern China and Singapore. Most of the remaining countries in the world – in the former Soviet space, the Middle East, the Americas, Africa, and much of Asia – are still in what might be called the “voyeur” world, still stabilizing, legitimizing or relegitimizing their governance regimes and institutions according to one tradition or the other, or indeed borrowing from both.

Argumentative (or democratic) governance is characterized by fairly elected governments that are constantly opposed, challenged or corrected by deeply ingrained institutions (like political oppositions, the courts or other levels of government) or broad estates (like the media, the academy, and various non-governmental organizations and groupings, not excluding religious organizations). Algorithmic governance, however, is characterized by the centrality of a smaller, select group of national “algorithm-makers” who, having been selected largely through intense filtering based principally on technical and intellectual (and perhaps ideological) qualifications (the so-called “smartest people in the room”), are constitutionally and culturally protected in their ability to generalize these algorithms throughout the country over the long run. Algorithmic governance lays claim to legitimacy via the securing of visible, concrete results in the form of consistently rising material wealth, advanced physical infrastructure, and general public order and stability – and indeed the rapidity (and even predictability) with which such outcomes are realized and real-life problems are solved.

Argumentative governance, on the other hand, maintains its legitimacy via procedural argument in the contest for power among political parties, and in the information provided to power via various feedback loops. A large number of these argumentative regimes are federal in nature (just as the number of federal regimes globally has grown markedly over the last couple of decades), and so centre-region relations are both another source of procedural argument and a type of feedback to power (from the local to the general or macro).

Figure 1: Key Characteristics of Argumentative, Algorithmic and Hybrid Governance

| |

Argumentative |

Algorithmic |

| Strengths |

- Procedural legitimacy

- Rich feedback mechanisms to political power

- Tendencies to constitutional decentralization, if not federalization (type of feedback mechanism)

- High marginal value of individual life

- More porous majority-minority relations

|

- Results-based legitimacy

- Highly trained, filtered and culturally respected and protected policy elite

- Capacity for long-term planning

- Capacity for rapid practical policy fixes

|

| Weaknesses |

- Weak long-term planning function

- Slowness (in extremis, paralysis) in delivery of practical results or in delivering practical policy fixes (“too much argument”)

|

- Weak feedback mechanisms to political power, resulting in “palace ignorance”

- Instrumentalization of individual life to the general algorithm

|

| Hybrid Governance (Future Possible Russian Scenario) |

- Development and recruitment/selection of bona fide policy elite (“algorithm-makers”)

- Development of long-term planning capability

- Deliberate fostering and protection of multiple feedback mechanisms to political power, including media, the academy, civil society, and among individual citizens

- Very gradual, deliberate decentralization, if not federalization (including for purposes of richer informational feedback to the centre)

|

What would hybrid Russian governance look like in the 21st century? Answer: It would draw on the obvious strengths of the dominant algorithmic and argumentative governance models, while guarding against the major weaknesses of each of these idioms. What are the key strengths of the algorithmic system that Russia should wish to adopt? First and foremost, Russia must invest in properly creating, over time (say, the next 15-20 years), a deep policy elite, meritocratically recruited and trained, to populate all its levels of government, from the federal centre in Moscow to the regional and municipal governments. Such a deep, post-Soviet policy elite is manifestly absent in Russia today, across its levels of government – a problem that repeats itself in nearly all the 15 post-Soviet states. Second, Russia must develop a credible long-term national planning capability (as distinct from the current exclusively short-term focus and occasion rank caprice of Russian governments, pace the various longer-term official national strategies and documents), led by the said algorithmic policy elite at the different levels of government, and implemented with great seriousness across the territory of the country. Third, Russia requires an intelligent degree of very gradual decentralization (rapid decentralization being potential fatal to national unity, or otherwise fragmenting the country’s internal coherence across its huge territory) and, if necessary or possible, a degree of genuine federalization of governmental power across the Russian territory (discussed further below). Fourth, Russia’s policy elites must foster the development (and protection) of many more feedback mechanisms from citizens to political power in both the federal centre and in regional governments – not for purposes of democratic theatre or fetish, but rather to avoid making major or even existentially fatal policy mistakes, or indeed to correct policy mistakes and refine the governing algorithms in the interest of on-the-ground results and real-life problem-solving (a major imperative in Chinese algorithmic governance today, where the governing elites, as with past Chinese emperors, are said to be “far away”). These feedback loops – from the media, the academy, various groups and, evidently, from all Russian citizens – help to ensure that even the smartest algorithm-makers in the future policy elite do not make catastrophic mistakes that are based on information that is wholly detached from realities on the ground in Russia, across its massive territory.

Thesis 2: Beyond the aforementioned decentralization, Russia should ideally federalize substantively, even if the country is, according to its extant constitution, legally and formally federal. At a minimum, as mentioned, the country must before long effectuate a gradual, controlled decentralization. Uncontrolled federalization or decentralization, of course, could lead to the breakup of the country or to generalized chaos (a fact well underappreciated outside of Russia) – so strong are the centrifugal and also regionalized ethnic forces across Russia’s huge territory and its complicated regional diversity. Unintelligent or careless federalization, for its part, could lead to excessive ethnic concentration, to the detriment of the legitimacy of the federal centre in Moscow, as well as to the overall governability of the country – including through the destruction of the critical informational feedback to the centre provided by citizens and local governments in decentralized regimes.

Critically, because there is no felt – instinctual or cultural, rather than intellectual – understanding of how federalism works in any of the post-Soviet states – most of which are not only unitary but indeed hyper-unitary states, built on strict “verticals” of power – it is perhaps appropriate (if not inevitable) that Russia should end up, through iteration and trial and error (the only way of doing policy in Russia), with what the Indians call a federal system with unitary characteristics.

Thesis 3: Mentality is critical to the future of Russia. There once was a “Soviet person”. What is a “Russian” person in the post-Soviet context? Answer: He or she is still being developed. The Soviet collapse left Russians with at least three types of anomie or general disorientation – strategic, moral and, to be sure, in identity. All three species must be reckoned with – not with fetishistic searches for single national ideas, but rather through deliberate investments in real institutions and public achievements, and through long-term, patient investment in the legitimation of these institutions and achievements, both inside Russia and, to a lesser degree, internationally. Indeed, part of this investment and legitimation must involve the fostering of a far deeper and more robust policy culture in Russia’s intelligentsia, among its still-venerable specialists in various professional disciplines, and also for its younger people, who are both the future algorithm-makers and also the future drivers of the feedback mechanisms that are essential to the effective governance of the country. Such a policy culture is dangerously underdeveloped in today’s Russia, which militates against effective pivots to either of the argumentative or algorithmic traditions, and indeed against the creation of a uniquely Russian hybrid governance this century.

Thesis 4: What of Russia and Europe this century? The conflict between the West (especially Europe) and Russia that erupted over Ukraine in 2014 and that endures, without foreseeable resolution and in multiplying manifestations, to this day, can be properly and fundamentally understood as what I would call an “interstitial problem” – that is, as the result of two regional regimes and geopolitical gravities (the European Union to the west and Russia and, more loosely, the Eurasian Economic Union to the east) pulling ferociously, in opposite directions, on a poorly governed space or theatre (Ukraine), with weak institutions and unstable legitimacy at its own centre (the said problem of the “youth” or “newness” of all post-Soviet states). How can this be fixed? Answer: by creating a “Europe 2.0” framework that interstitially – and tendon-like – binds Moscow with Brussels, or indeed the Eurasian and European planes, via Kiev. The “thickness” of the binding mechanisms may well be de minimis to start – that is, comprising strictly confidence- or trust-building measures and economic exchange, evolving possibly over time to security and political arrangements.

To be sure, with the European Union weakened, if not existentially compromised, by several concurrent crises (Brexit, refugees, economic stasis, the Ukrainian crisis and Turkish authoritarianism at its borders, and the serious prospect of more Eurosceptic governments on the Continent), an emerging strategic perspective from Moscow would seem to be that even the “European” option or pivot is now no longer on the table for Russia, even if the vision of constructing a common space between Lisbon and Vladivostok has been, with varying degrees of intensity and coherence, in the strategic psyche of, and expressed in many public statements by, Russian leaders going back to Mikhail Gorbachev (“Big Europe”) in the late Soviet period to Vladimir Putin from the early 2000s.

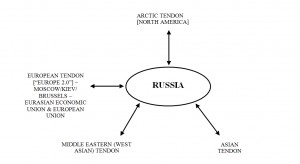

Having said this, as Europe 1.0 transforms, it seems inevitable that, if peace is to be maintained on the continent, and if Russia is to avoid accidental or even narcissistic isolation and find economic and intellectual openings to Europe, then this Europe 2.0, even if it seems improbable at the time of this writing, will still have to be “invented”. As such, there is a distinct strategic opportunity here for Moscow, if it is smart and plays its cards properly, to play a key role in its formulation and erection. Indeed, as Russia, on top of its juxtaposition with the European Union, shares borders with several existing or emerging or potential economic and political blocs or international regimes in Asia, the Middle East and even, via the melting Arctic, North America (a juxtaposition still underappreciated in North American capitals), Russia has an opportunity to play a pivotal role in constructing a wide array of interstitial bridges and mechanisms that would help to both give its strategic doctrines greater and more constructive focus, and also help to drive the country’s institutional and economic development this century (see Figure 2). Moreover, to the extent that collision between two or more of these international blocs or regimes may, as with the Ukrainian case, lead to conflict – including, in extreme scenarios, nuclear conflict early this century – then the opportunity for intellectual and strategic leadership in such interstitial “knitting”, as it were, by Russia assumes a world-historical character.

Figure 2: Russia’s Interstitial Links to Key Global Theatres

(click for bigger image)

Thesis 5: Russia has a serious succession problem. If this is not negotiated properly and carefully, it could result in civil conflict or chaos, and even the breakup of the country into several parts. (This is a fact, as mentioned, that is deeply misunderstood outside of Russia.) The absence of “argumentative” institutions in Russia, including the peculiar weakness of its political parties, means that the identity of, and nature of the contest and process for determining, the next President and other strategic leaders of Russia are not (uncontroversially) clear. This, again, is not a question of democratic fetish, but indeed one about the ability of the centre in Moscow to project legitimacy across the entire gigantic territory and population of the country. In the absence of a process deemed legitimate and a person who, in succession to President Putin, is able to command the agreement of the masses to be governed by him (or her), then there is a non-negligible risk of civil destabilization of the country. What’s more, should the presidency end more suddenly, for whatever reason, then the country could be seriously destabilized, as the process of relegitimation of the centre in succession will not have been triggered in time.

It is in the interest of Russian leaders to make the succession process extremely plain to the Russian people immediately. It is also manifestly in the interest of outside countries to understand this succession challenge – not least in order to be disabused of any interest in destabilizing the Russian leadership artificially, in the knowledge that a weak governing legitimacy in the aftermath of President Putin could create not only wholesale chaos in Russia, but indeed major shockwaves in global stability (beginning at Russia’s borders and radiating outward).

Thesis 6: The creation of a true policy elite in the Singaporean or Chinese algorithmic idiom requires significant and long-term investment in education, and the creation of top-tier educational institutions, from kindergarten to the post-secondary levels. The USSR, for all its warts, had these (including “policy” and administration academies through its Higher Party School). Russia, as a new state, does not. On top of world-class institution-building in education, Russia must, in order to improve the feedback mechanisms of the argumentative tradition, invest in, and deliver, renewed institutions of politics (including federalism), economics (including credible property rights protection), the judiciary (including serious judicial protection of the legitimate constitutional powers of different levels of government), as well as other spheres of Russian social life, including the religious sphere.

Thesis 7: How to solve the Ukraine conflict and, by extension, Russia’s conflict with the West? I have written about this extensively, in many languages, and confess that the window for any clean, comprehensive resolution of this conflict may by now have passed (something both leading Russians and Ukrainians know fairly well, even if some Western analysts may not yet). In 2014 and 2015, a winning algorithm for resolution, on my assessment, would have seen the insertion into the Donbass region of neutral peacekeepers (for example, from a respected Asian country like India – that is, non-NATO, but also not post-Soviet), constitutional reform in Ukraine (including possible federalization in toto – recalling the aforementioned need for most post-Soviet states to decentralize or federalize – and/or special status or special economic zones for several regions of the south and east of Ukraine, in concert with the enshrinement of an indissolubility clause for the Ukrainian union in the national constitution, as in Australia’s constitution), and strong guarantees on the permanent non-membership of Ukraine in NATO (including through a possible UN Security Council resolution). These steps would have been accompanied by the removal (at least by the European Union) of economic sanctions not related to Crimea.

The paradox of the Ukraine conflict at the time of this writing is as follows: Ukraine cannot succeed economically or even strategically without re-engagement with Russia (no amount of Western implication will make up for the loss of Russian engagement); Russia cannot succeed (or modernize) economically without the removal of sanctions (and without a deeper reconnection with the European Union); and the coherence of Europe suffers for the disengagement and economic weakness of Russia, as well as for the Ukrainian crisis at its borders. No resolution is currently in sight because both Ukraine and Russia remain “two houses radicalized” in respect of this conflict, with key Western capitals not sufficiently understanding (or believing) the finer details of the conflict and its genesis, with Moscow gradually becoming “used to” the economic sanctions and renaissance of tensions with the West (including in its domestic political narrative), and with the government in Kiev increasingly unstable and therefore unable either to deliver major domestic reforms or to make decisive moves in respect of resolving the Donbass war. Moreover, the accelerating disintegration of the Middle East, in Syria and beyond, has grossly complicated any prospects of exit from the crisis – effectively fusing together the European theatre with the Western Asian theatre.

Leaving aside the succession issue in Russia (Thesis 5), there is a clear risk of systemic collapse in one or both of Ukraine (for political and/or economic reasons) and Russia (for economic reasons) in the near to medium term. Collapse of either country’s system would be devastating for both countries, as well as for European and global stability (including in nuclear terms).

Only a systemic solution is possible to the conflict, and yet I do not believe that Europe is currently sufficiently strong and united to be able to drive a solution. The United States, for its part, is politically unable to relieve Russia of sanctions, and so Moscow will not see much utility in the American play except insofar as Washington can play a role in pushing or incentivizing Kiev to make or not make certain moves. As such, the “solution” to the conflict can for now only be partial, rather than general and global. And in my assessment, it is Asia – particularly China, and perhaps also India – and not Western countries that must play the pivotal role. (Indeed, Moscow could cleverly seduce both New Delhi and Beijing, geopolitical rivalry between the two oblige, to play co-leads in this partial resolution.) The two key elements of the winning partial algorithm could include:

i. neutral peacekeepers from a leading Asian country and police or constabulary force in the Donbass and along the Russia-Ukraine border; and

ii. heavy Russian state reinvestment into all of Ukraine, and, concurrently, heavy Ukrainian reinvestment into all of Russia, with both countries combining economically to rebuild the Donbass in particular – all with significant loan guarantees from the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the new BRICS bank, as well as by the Indian and Chinese governments proper (with opportunistic but subordinate participation by other states as they see fit).

Issues like NATO guarantees of non-membership for Ukraine and also the future status of Crimea, as well as global sanctions relief for Russia, all require deep and coherent Western engagement, and so are not on the table for the foreseeable future. The above algorithm also insulates the Ukraine conflict somewhat from the Middle Eastern conflict – or, in other words, delinks, diplomatically, the resolution of the Ukraine conflict from that of the various, arguably less soluble Middle Eastern theatres.

Thesis 8: Despite its cultural dynamism and its deep intelligentsia, Russia’s economy is unacceptably primitive. Natural resources and energy products will continue to dominate Russia’s economy for the foreseeable future, just as they did in the last century – which also makes the national economy and the federal and regional budgets exceedingly vulnerable to commodity prices swings (as at the time of this writing). However, what appears to be missing in Russia today, in addition to proper investment in infrastructure across the territory, is a matching of state purpose, deep entrepreneurial talent, and large-scale venture investment in Russia in export-oriented sectors outside of commodities – the predictable result of which is a disproportionate dearth of great and global Russian companies and brands (again, outside of the commodities sector). And so here the model for Russia is likely Israel, from which algorithmic countries like Singapore have borrowed heavily in fashioning their own state-private sector models. Applied to the Russian context, that model would seem to commend two critical reform vectors for Russian industrial policy (which is far more important here than, say, tax policy): first, the creation of a handful of national educational, military or technical-scientific institutions (elite or quasi-elite) that are able to fashion an achievement-oriented mindset among Russia’s young adults, as well as deep, lifelong friendships and networks among these people; and second, assurances that the Russian state, with minimal bureaucratic friction (a perpetual challenge in its own right in Russian public administration), is positively disposed to giving entrepreneurs from this “class” of young achievers passing through these institutions a first contract (procurement), initial funding, or indeed future contracts of scale.

In Israel (and also Singapore), it is often the military that serves this “bonding” and “maturing” function among young (future) achievers, including among future entrepreneurs, while in a country like the U.S. the Ivy League elite universities play a similar role. When young Israelis complete their compulsory military service, they typically are, by comparison with their international counterparts, more mature, more confident, more bonded or networked with future partners in life projects (including business ventures), and have had “real” or “consequential” experience in fields like computer science, engineering or logistics. Now, after they finish their university studies, and as they start different entrepreneurial ventures, the state plays a key role in providing initial liquidity or contracts for purposes of giving momentum to startups, and eventually for purposes of developing scale. Importantly, the state is often prepared to lose some bets on some of these companies in the knowledge that it and the country’s economy will likely win big on other bets (or on a broad sample of bets).

Thesis 9: A key aspect of the argumentative paradigm of governance is that the marginal value of human life is greater in the societal geist of argumentative states, given the high importance ascribed to procedure and also feedback to political power from citizens. This larger marginal value of life is given expression through very robust constitutional and cultural bulwarks for protecting human life, which is viewed in absolute terms. By contrast, algorithmic states, especially of the Asian ilk, may, at least implicitly, attach greater instrumentality to human life – that is, human life as being in the service of, or subordinating to, the preferred Asian freedom (not freedom from government repression, but instead freedom from chaos). The Singaporeans and Malaysians, for instance, refer to the fear of chaos and death, in the Hokkien idiom, as kiasi, in response to which extreme or radical private or public measures may occasionally need to be taken: consider the death penalty or, more commonly, the standing use of emergency laws and measures. An individual life or, short of that, what Westerners view as fundamental rights, may, on this logic, need to be compromised or traded in the service of the more important general protection and freedom from chaos. This may lead to swifter and less compunctious resort to peremptory punishment (like the death penalty) for what might, in the argumentative states of the West, be considered micro-torts (including some drug offences), or to draconian emergency laws and prerogatives in response to perceived threats of a political ilk (including terrorism).

The policy implication for Russia is that the “care” given to each individual Russian citizen (or the value of the individual Russian life) can be improved indirectly or circuitously – that is, that improvement may come not necessarily through direct legislative or regulatory changes (and certainly not from well-intentioned rhetoric and nice proclamations), but indeed through investment in some of the “argumentative” institutions themselves – including improvement of the health and sophistication of the various estates, from political parties to Russian civil society (and even Russian businesses), that provide the feedback mechanisms from the governed to the governors, and thereby remove some of the edge from the bureaucratic leviathan as it touches the human condition.

On this same logic of increasing the value of individual life, increased investment in argumentative institutions can arguably lead to better, more porous relations between the ethnic Russian majority and the many important minorities of Russia. A somewhat less classical, more citizen-oriented conception of, or approach to, national security and public safety and criminal justice is also instructive in this regard.

Thesis 10: Excellent Russian public policy and administration will never wholly eliminate Russian public corruption. Russian corruption – narrowly conceived – can, to a limited extent, be seen as an informal institution of Russian state and society. In this, Russia is not that far removed from many countries and societies around the world, including in the more advanced countries of Northeast and Southeast Asia. Instead, the key question for Russian statecraft in the early 21st century is whether, allowing for limited corruption as an informal institution, the governing classes can move the country to greater wealth and stability, and improve meaningfully and substantially the daily lives of citizens. Manifestly, it would be best to improve the lot of citizens with negligible corruption, as is the standard in the argumentative states of North American or Western Europe. And just as manifestly, it is unacceptable to remain corrupt while the quality of life for Russians stagnates or deteriorates. But the story of leading algorithmic pioneers like Lee Kuan Yew or, on a more serious scale, Deng Xiaoping, is not one of perfunctory non-corruption – as that would likely remove all lubrication from the administrative system, institutional inertia oblige – but instead public achievement and policy-administrative delivery to citizens in the context of significant corruption that, over time, enjoys a downward trajectory.

The paradox of Russian public administration as it applies to matters military versus non-military is instructive in this regard. In Russia, short-term military or emergency orders or decrees (or algorithms) – especially ones involving actual military missions – are typically dispatched with remarkable rapidity and efficacy (demonstrating a prodigious organizational ability to scale very quickly). And yet long-term plans and projects (including even military procurement) are delivered with notorious inefficiency, slowness and procedural corruption. For these long-term projects, presidential decrees are issued, with considerable regularity, to even repeat or remind the bureaucratic system about the existence of still-unfulfilled erstwhile presidential decrees. Quaere: what type of strategic, policy and administrative seriousness and quality would Russia need to be able to deliver on the long term but prosaic with the same inspiration with which it delivers on various emergency prerogatives? Can the country maintain its focus (and cool)? Can it develop a professional leadership class across the country, at different levels of public power, that has a “synoptic vision” that is sufficiently vast to incorporate Russia’s endless complexity while constantly iterating and refining this vision through citizen input and feedback? Can this class of people both populate and in turn discipline the administrative apparatus of the state? And, whatever the compromises it may require en route, can it deliver the goods for the Russian people?

Irvin Studin

Irvin Studin